Learning Connection

Page Navigation

What does literacy look like in Blue Valley?

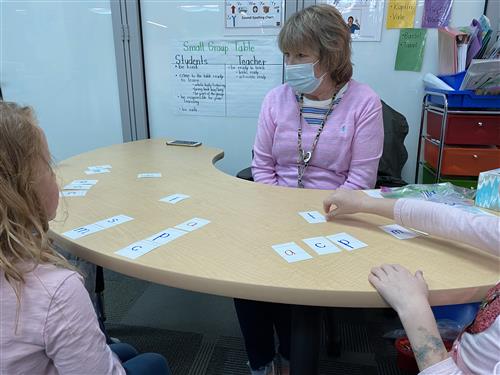

At the beginning of the school day in kindergarten teacher Sue Rassette’s class, students are divided into small groups as they rotate through stations and focus on literacy.

While some groups are working on literacy on tablets or collaborating on an activity, they each spend a rotation with Rassette, a teacher at Prairie Star Elementary, as they work together on identifying vowels and consonants.

Rassette pulls out a small deck of cards, individualized to fit each student's needs. She says a word, asks the students to stretch out the sounds, then spell it using the cards in front of them. Then they sound it out and read the word.

Kindergarten is one of students' first introductions to reading, writing and spelling. In Blue Valley, students are learning through a structured literacy approach that utilizes multisensory learning experiences.

What is structured literacy?

Structured literacy concepts are taught in a way that allows students to form lasting connections to sounds, symbols and meaning in the brain. This approach is based on the science of reading, a thorough research body articulating how the brain learns to read and what it does as a person reads.

There are five facets to the teaching and learning of literacy in Blue Valley — phonology (hearing and manipulating sounds), sound-symbol (connecting sounds to letters), syllables, morphology, syntax and semantics. Students and teachers may refer to these concepts collectively as phonics.

Structured literacy creates a diagnostic, explicit, systematic and cumulative learning process.

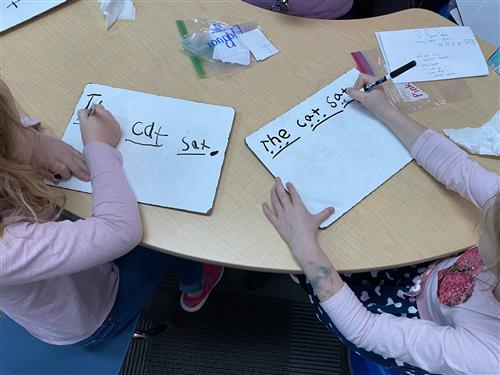

Teachers are focused on teaching students how to encode and decode words. Decoding is learning how to read and pronounce words. Encoding is the process of connecting sounds to letters then spelling words.

The approach to teaching high-frequency and heart words has changed as knowledge of how children develop as readers evolve.

Students aren’t just given a list of words and asked to learn them through repeated whole-word reading or memorization.

Instead, teachers are working with students on high-frequency words that are decodable (to, she, that) and undecodable heart words (said, could, their, because.) Heart words have letters in the words that do not follow the phonics rules and students must learn these parts of the words by heart.

In kindergarten, students’ learning begins with a focus on hearing high-frequency words in oral language. They quickly move to seeing the words in print. This leads students to map the sounds in these words to the symbols, or letters.

“They learn the individual sounds and letters through sound-spelling mapping,” said Christy Rottinghaus, Blue Valley’s K-12 literacy district coordinator. “Eventually they write the words using their phonics skills. Their brains are orthographically mapping these words throughout this process. So it’s not a ‘Boom, you memorized it.’ It’s truly making a lasting connection in the brain.”

Students learn, practice and review high-frequency words many times, and that repetition is key to using them in their language and writing.

Students have always learned syllables and how to break apart words. Structured literacy makes the learning explicit and focuses on using knowledge of the six syllable types to decode, pronounce words, write and spell.

This learning starts in the primary grades, but continues through elementary as students encounter more complex text, especially in science and social studies. First through fifth graders are learning hand signals for syllable types.

These hand signals incorporate the multisensory approach of structured literacy. If a student forgets a letter sound or syllable type, their teacher can help them recall it by reminding them of an assigned hand signal or keyword.

“Now students are utilizing syllable knowledge more than ever before,” Rottinghaus said. “This allows them to break apart unfamiliar words when reading rather than guessing.”

As students progress through grade levels, they study more complex English language skills, such as morphology. Beginning in second grade, students learn morphology, the study of meaningful units of language and how they are combined to form words.

Prefixes, suffixes and Greek and Latin roots and bases are major components of this concept. Students use this knowledge to understand the meaning of words they encounter in text while reading.

Erika Haas, a third-grade teacher at Prairie Star, has been working with her students on morphology and how to build words using prefixes, suffixes and root words.

“I’ve definitely seen a lot of growth from the first day to where we are today,” Haas said. “I think the lessons have helped them when they are reading a novel to figure out how to attach a word and figure out how to read the words.”

Teaching students syntax, the understanding of how words are organized in oral and written language as well as semantics, allows teachers to target the skills kids are missing while developing their skills for more advanced writing and communication.

Christy Auvigne, a fifth-grade teacher at Cedar Hills Elementary, said the spelling and word understanding among her students has been exponential.

“My students' ability to spell, their ability to split syllables apart and their ability to recognize word parts is much better than it’s been in the past,” Auvigne said.

Multi-sensory approach beneficial to all learners

A multi-sensory approach is essential to students who have dyslexia or struggle to store and retrieve information in the brain.

“The multi-sensory approach of showing a hand signal or thinking about a keyword that represents a letter helps make connections in the brain rather than giving those students the answers so they can get it quicker,” Rottinghaus said. “We ask them key questions so they retrieve it from the brain.”

Teaching students using an explicit, systematic and cumulative approach will help them build a solid phonics base. With these skills in place, readers can focus on comprehending what they are reading.

Blue Valley’s reading specialists are key to helping struggling readers excel. During the implementation of structured literacy, district reading specialists also spend time in classrooms to work in small groups or co-teach to support the learning.

Morgan Irwin, a reading specialist at Prairie Star, works with multiple small groups of students each day.

During a session, and dependent on the needs of each student, Irwin may work on letters with a multi-sensory approach by having them say the letter then write the letter with their finger on a tactile piece of paper or in sand.

The students are also sounding out words, saying what sound the letter makes then writing the letter.

Structured literacy and multi-sensory learning don’t just benefit struggling readers. Blue Valley teachers said students’ fine motor skills are better and they are learning true letter formation across all grade levels.

“When you have strong fine motor skills you write more automatically,” Rottinghaus said. “The way students are learning their letters, sounds and syllables is allowing them to continue to develop as readers while helping them be better spellers and writers.

Blue Valley teachers are seeing many improvements in students’ understanding of reading, writing and spelling. The automaticity of these skills makes them more fluent readers and writers.

“Teachers are adjusting and implementing structured literacy into their daily lessons, making it more multisensory as they teach skills from simple to more complex,” Rottinghaus said.